Understanding the full impact of smoking on critical illness

News Article

Publication date:

12 February 2020

Last updated:

25 February 2025

Author(s):

Adam Higgs

Understanding the full impact of smoking on critical illness & the incidence rates across different smoker status.

It is no secret that smoking is not good for you. Across the years there have been a multitude of facts and figures published around increased risks to certain conditions and the impact of smoking on longevity. When recommending critical illness, it is important to understand what conditions a client is most susceptible too in order to understand which insurers may offer broader coverage in these areas.

Protection Guru has recently extended the analysis provided via our sister QualityAnalyser.com site which allows advisers to look in detail at which Critical Illness policies are most liken to pay out over the term of a policy for an individual based on their age, gender and now whether the individual is a smoker, former smoker or has never smoked. Our medical experts tell us this is a more accurate than just looking at if the individual is a current or former smoker. This data can now also be accessed via the new Product Features report in iPipeline’s Solution Builder multi benefit comparison service https://uk.ipipeline.com/products/solutionbuilder/.

Clearly a person’s smoking status will mean that they may have a higher propensity to suffer from certain conditions. In this insight we explore the work our doctors have carried out in this area and highlight what conditions are most affected by smoking.

Cancer

It is no surprise that smokers have a higher prevalence of Cancer than people who have never smoked. Studies have shown that there are actually 15 different cancers associated with an increase in risk from smoking exposure, as listed below:

- Lung

- Oral Cavity

- Pharynx

- Oesophegeal

- Stomach

- Liver

- Pancreas

- Colon

- Rectum

- Larynx

- Cervix

- Ovary

- Bladder

- Kidney

- Acute Myeloid Leukaemia

Whilst smoking can increase the risk of suffering from all of these cancers there are a few that are more common and as expected those that stop smoking can reduce their risk as our panel of independent medical experts explain:

“Smoking has been shown to increase the risk of 15 different cancers, with the most common being lung, bowel and bladder cancer. This is caused by the chemicals in cigarette smoke changing the DNA of the cells in the body, which could potentially become cancerous. Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death, with smoking thought to cause 70% of all lung cancers in the UK. There are large reductions in cancer risks for smokers that decide to quit. After five years, the risk of cancers of the mouth, throat, oesophagus, and bladder is roughly halved. Also by this point, cervical cancer risk falls to that of a non-smoker. Even for lung cancer, the risk will have halved after 10 years of smoking cessation.”

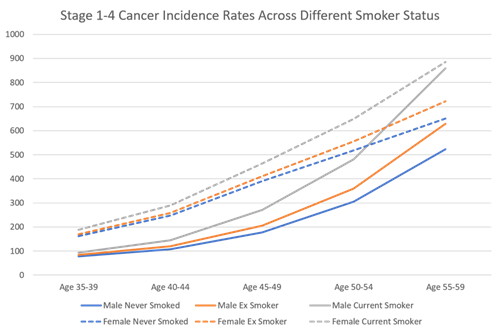

As with most conditions covered under critical illness policies, the risk of cancer increases the older a person is. The graph below highlights what the incidence of cancer is in both males and females over different age ranges depending on whether they are a current smoker, ex-smoker or have never smoked.

Heart Attack and Stroke

Cancer, however is not the only condition where smoking increases risk. Blood vessel damage is also an area where problems can occur as our doctors explain;

“Tobacco smoke contains around 7,000 toxic chemicals. These chemicals get into the blood stream through the lungs and damage cells throughout the body. Cigarette smoke changes cholesterol levels in the body, increasing LDL cholesterol (the bad type) and decreasing HDL cholesterol (the good type). This increases risk of both heart attacks and strokes.

The nicotine in cigarettes also increases the heart rate and blood pressure, and carbon monoxide decreases the ability to carry oxygen in the bloodstream. In addition, some of the chemicals can affect the platelets (clotting cells), which makes blood clots more likely. All the above, increases the risk of atherosclerosis, which is where plaques form in the arteries in the body, reducing blood flow and increasing the risk of heart attacks and stroke.”

Ischaemic Heart Disease

Whilst critical illness covers many different conditions, they also cover certain surgical procedures. For many, these are listed as separate definitions depending on the type of surgery or area of the body being operated on. The direction of travel seems to be to provide a definition that covers a number of surgeries, such as Scottish Widows’ Heart and vascular surgeries of major/minor severity and smoking will affect the risk of someone requiring one of the coronary surgeries;

“Cigarette smoking approximately doubles the risk of morbidity and mortality from ischaemic heart disease compared with somebody that has never smoked. The overall risk is dependent on the duration and amount of smoking. For smokers under the age of 50, the risk of developing coronary heart disease is 10 times greater than for those of the same age who have never smoked. The risk of ischaemic heart disease will roughly halve after one year of stopping smoking, compared to if smoking had been continued.”

How have we incorporated this into our critical illness analysis?

Within our critical illness comparison tool, Quality Analyser and now in iPipeline SolutionBuilder, we use incidence data that is gender and age specific. This incidence data tells us the proportion of people (usually X in 100,000) of a certain gender that have suffered from a given condition at different age ranges. This data is usually based on whole of population so will include smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers. In order to distil the specific incidence of these three category of people, our panel of independent medical professions needed to obtain data on the increased risk that smokers will incur if they smoke along with the proportion of the population that fall into each category. There is clearly some complicated maths to calculate this, which is far too much for one insight, however our doctors have given a brief explanation of how this is done below;

“Disease incidence is constantly changing, often due to the population’s exposure to modifiable risk factors. For example, in the last 10 years, the prevalence of exposure to smoking has dropped significantly by around 10%.

When looking at how UK population incidence data is affected by smoking, it is important to review current meta-analysis of population cohort studies to try and establish relative risk data. This will compare the likelihood of a disease developing between two groups, in this case those that have been exposed to smoking (or previously exposed), and those that have not. In order to apply this to incidence data, it is also important to establish the risk factor exposure prevalence; on these terms, the percentage of the population that are smokers or ex-smokers. We will update the exposure prevalence annually, to allow for the ever-changing trends in smoking in men and women.”

From this, the PAFs (population attributable fractions) can then be established, which can finally be applied to the general population incidence figures to calculate how the incidence data will change in the exposed and unexposed group.”

Helping people understand the conditions they are most likely to suffer from based on their own personal circumstances can clearly be a great aid when considering critical illness. Combining this information with a panel of independent medical experts view of the likelihood of being able to claim if diagnosed with one of these conditions is even more powerful when assessing the most comprehensive product for that particular client, hence this significant extension to the data included within our Quality Analyser tool and now our analysis in the iPipeline’s SolutionBuilder’s Product Features Report.

To sign up to the Protection Guru mailing list you can register your details HERE

This document is believed to be accurate but is not intended as a basis of knowledge upon which advice can be given. Neither the author (personal or corporate), the CII group, local institute or Society, or any of the officers or employees of those organisations accept any responsibility for any loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of the data or opinions included in this material. Opinions expressed are those of the author or authors and not necessarily those of the CII group, local institutes, or Societies.